For day traders, both profitable and unprofitable, tax concerns are one of the most criminally overlooked issues.

Why? Because aside from trading itself, taxes have the most material impact on your profits than anything else.

FIFO (first-in, first-out) and LIFO (last-in, last-out) are inventory accounting concepts. Your local grocery store probably utilizes FIFO to manage their inventory.

Do you know how the newest and freshest containers of milk are in the back of the fridge? That’s due to FIFO. Grocers keep the oldest milk out front, so they sell the oldest stuff first, hence “first-in, first-out.”

The same concept applies to selling stock under a FIFO designation.

If you accumulated the same stock over several weeks, buying in separate lots, then sell, you’ll sell the shares you bought first.

Likewise, in LIFO (last-in, first-out), you’d offload the shares you most recently acquired when you sell.

Depending on your holding period, your portfolio’s performance, and your trading style, choosing either FIFO or LIFO can have severe tax implications for your portfolio, so they’re concepts worth understanding, even if you allow your tax prepper to handle everything.

How Capital Gains Taxes Work

Proceeds from asset sales incur capital gains taxes. Generally, profits on sales are subject to taxes, while losses can be written off against other income.

In the United States, there are long-term and short-term capital gains taxes, with short-term gains being taxed at a higher rate. All day trading profits are subject to short-term capital gains taxes.

As a consequence, profitable day traders have significantly higher tax burdens than long-term investors.

A genuine long-term Warren Buffett-style long-term investor can defer paying taxes on their investments for years, as they only pay taxes when they sell.

Long-term capital gains are also lower across the board, regardless of income bracket.

Taken from Investopedia, here are the long-term capital gains tax rates in the US, by income bracket:

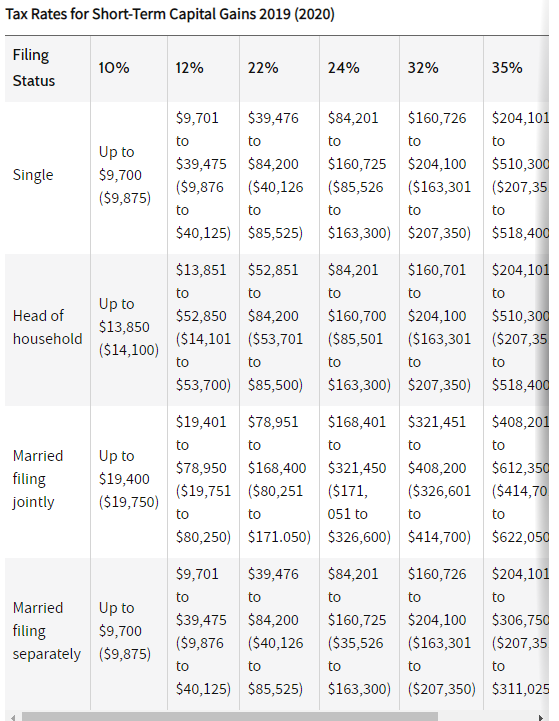

Here are the short-term capital gains tax rates:

That last bracket is cut off, which is 37% for Singles and Married (filing jointly), making over $510,300, and $612,350, respectively.

What is FIFO?

FIFO is an acronym for first-in-first-out. Put simply that means the first shares acquired are the first sold.

FIFO is an accounting and inventory management term to determine cost basis.

For example, let’s say you own 100 shares of Company XYZ, acquired in two separate 50-share lots with the first purchase in September 2020 and the second in October 2020.

If you were to sell 50 shares using the FIFO method, your broker would designate the first shares (purchased in September) for sale. Hence the name first-in-first-out.

Unless you specify otherwise, the IRS will assume that shares are sold on a FIFO basis.

Example in Apple Stock

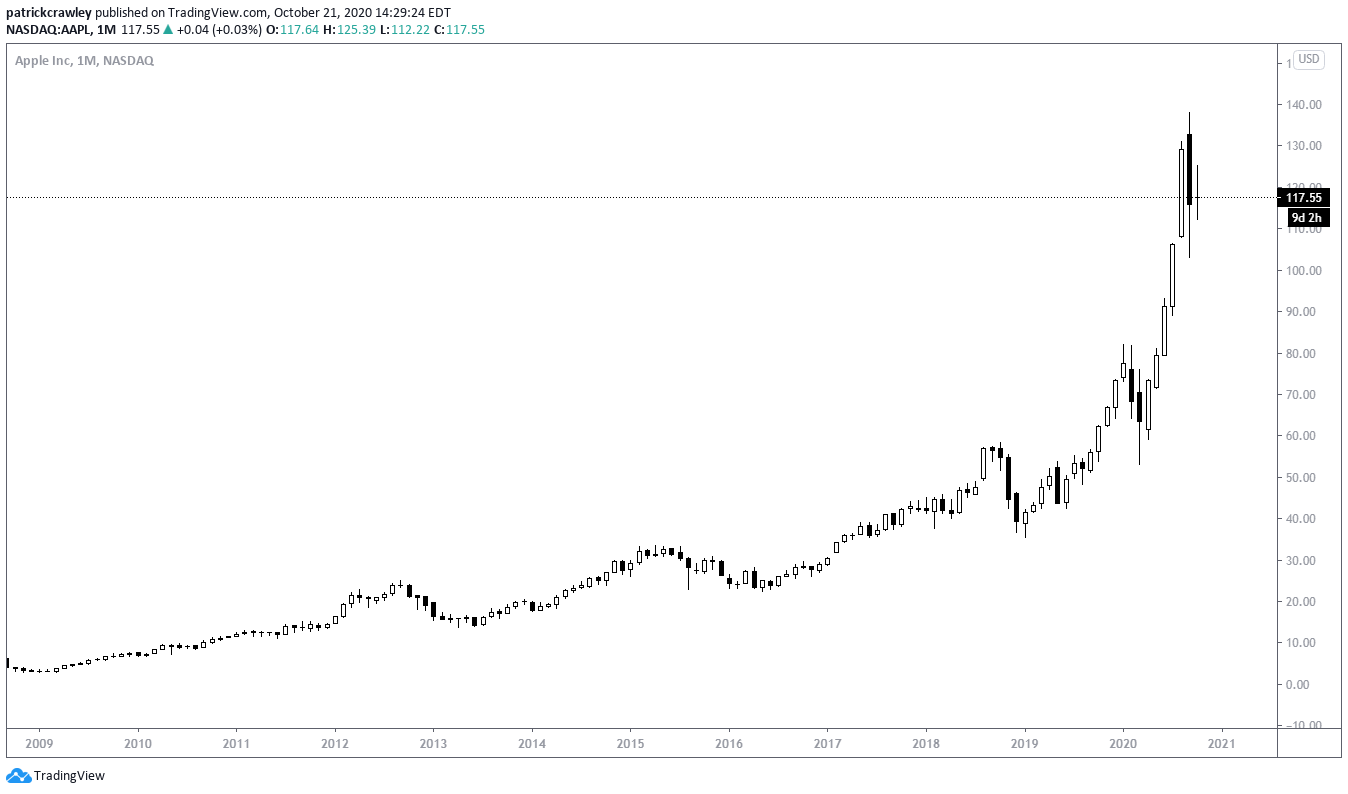

As you stretch out the timeframes, FIFO can dramatically affect the tax implications for long-term investors. Perhaps you’ve been building a long-term position in Apple (AAPL) stock over the last decade, buying more shares each year.

As the stock has multiplied several times since then, you opt to sell some shares to lock-in profits.

Let’s assume you’ve been buying 100 shares each year, and you now have a 1,000 share position. If you sell 100 shares, you will sell the first lot you purchase in 2011 between $10 and $15 (split-adjusted).

While these shares would, of course, qualify for a long-term capital gains tax rate (holding period longer than six months), you’d be paying taxes on roughly $100 per share in profits.

Why Use FIFO

FIFO is typically the default tax lot designation for most brokers and trading platforms. If you don’t specify a different inventory accounting method in your tax returns, the IRS will assume you’re using FIFO.

As such, if you don’t have a compelling reason not to use FIFO, using it won’t cost you any extra time or legwork.

What is LIFO?

LIFO is the opposite of FIFO. It’s an acronym for last-in-first-out, which translates to selling the shares you most recently acquired.

Why Use LIFO?

If you sell a portion of your positions on the way up, using LIFO to calculate your cost basis is probably the most advantageous.

An intermediate-term momentum trading style like that of Market Wizard Mark Minervini is a perfect example of where LIFO might be useful.

Your holding period is a significant determiner of whether or not considering LIFO would be favorable to you come tax season. If your average holding period exceeds one year, LIFO probably doesn’t make sense.

This is because, under FIFO, the profits on your first-in shares would be taxed at long-term capital gains rates, as opposed to under LIFO, your last-in shares (most recently acquired) might fall under short-term capital gains (which are taxed at ordinary income rates).

Calculate FIFO vs. LIFO

You could pontificate all day about the benefits of different inventory accounting methods.

Still, the decision is so unique to your own trading style and holding period that it’s probably the best for you to crunch some numbers on a few of your recent trades and see which benefits you.

Here’s a FIFO and LIFO calculator from Calculators.Tech. You could then apply your capital gains rates to the proceeds from trade and see which one is most advantageous to you.

Bottom Line

There’s a reason FIFO is not only the IRS’ default but the default of most brokers and trading platforms. It’s simple and tends to benefit most investors.

However, there are times where something different makes sense. And by the way, for individual stocks, there are other inventory accounting methods like the specific-shares method, which might also make sense.

As always, with complex tax matters, consult a CPA or financial advisor to really understand the nitty-gritty of these matters and help apply them to your personal situation.

The post LIFO vs FIFO: Which is Better for Day Traders? appeared first on Warrior Trading.