The max risk in a calendar options spread is the debit paid for that calendar, provided that the trade is exited at or before the expiration of the near-term option.

That may not be completely obvious if you hear it for the first time.

In this article, we will prove this is the case.

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

- An Example Using A Put Calendar

- What About Call Calendars?

- Conclusion

-

-

-

-

-

An Example Using A Put Calendar

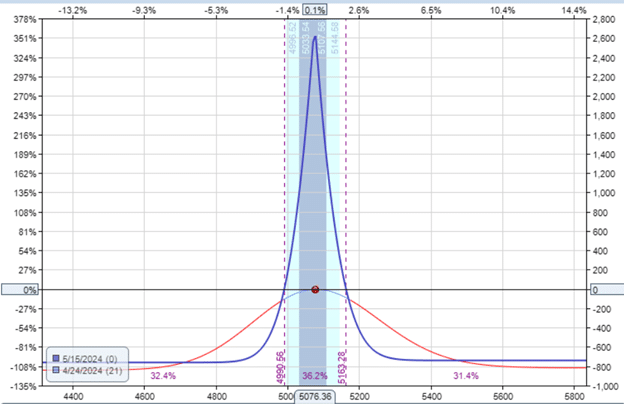

As modeled by OptionNet Explorer using historical pricing, the following is an at-the-money put-calendar on SPX purchased on April 24, 2024…

Date: April 24, 2024

Price: SPX @ 5076

Sell one May 15 SPX 5075 put @ $60.75

Buy one May 22 SPX 5075 put @ $68.15

Net debit: -$740

Delta: 0.09

Theta: 24.50

Vega: 75.06

The near-term short put option expires in three weeks.

And the far-term long put expires one week after that.

We are concerned with the worst-case scenario at the expiration of the near-term option – in this case, on May 15.

Suppose that SPX rallied up and the price of SPX was above the calendar at, say, 5400 on May 15.

In that case, the short put would have expired worthless, and the long put would still have some value left in the option.

The point is that the trader would have no obligation to fulfill at expiration.

The short put option is an obligation to buy at the strike price if the underlying price is below the strike price.

In this case, the price is above the strike price, so there is no obligation.

No money changes hands.

The trader is only out of the debit that was paid for the calendar.

In fact, the trader could recoup some of that debit by selling the long put for whatever value is left there.

Even if the trader decides not to sell the long put option, and if, in the worst-case scenario, the long put option becomes worthless, the trader is not any worse off than losing the money he or she paid initially for the calendar.

What if the SPX price had dropped way below the calendar – say at 4800 on May 15?

In that case, the trader does have an obligation due to the short put option.

The trader must “buy” the SPX index at 5075.

The word “buy” is in quotes because one can not buy the SPX index.

It is cash-settled.

If the market price is 4800 and the trader buys at 5075, the trader is out $27500 as calculated by (5075 – 4800) x 100.

If the trader had only the short put option, that would be the amount the trader lost.

Fortunately, the trader has a long-put option with a strike of 5075.

This long put entitles the trader to sell at 5075.

The trader utilizes the long put to “sell at 5075” to fulfill the obligation to “buy at 5075”. It is net zero.

Both short and long put options are gone at the expiration of the near-term option.

All that the trader loses is the debit originally paid for the calendar.

Now we understand the importance of the long put option and remember never to sell the long option of a calendar without first removing the obligation of the short option.

What is more typical is that a trader will close the two options simultaneously in the same transaction to exit the calendar trade.

What About Call Calendars?

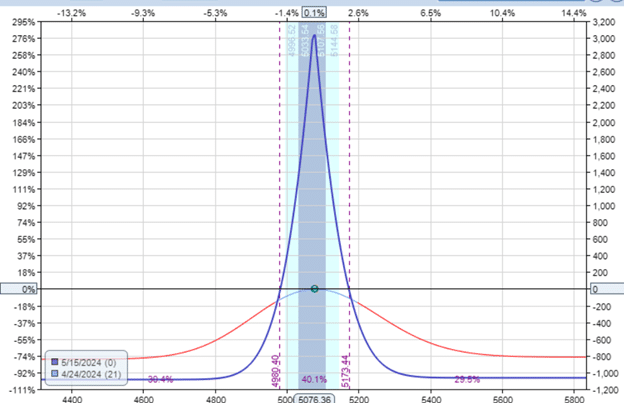

A call calendar on April 24 would have cost $1085 and would look like this:

Delta: 0.1

Theta: 24.5

Vega: 75

It had the same expirations and strikes as the put-calendar.

It cost a bit more at $1085 versus $740 due to the put-call skew in the SPX.

Let’s perform the thought experiment to see that the worst-case scenario is where the maximum loss is the cost of the calendar.

If SPX is above the call calendar on May 15, then the short call option is in-the-money.

The trader is obligated to “sell” at 5075.

The trader utilizes the right of the long call option to “buy” at 5075 to perform the obligation to sell at 5075.

Both options are gone, and the trader loses the money initially paid for the calendar.

If the price of SPX is below the calendar, the short call option expires worthless.

The trader is left with a long call that can be used however he or she wishes.

In the worst case, the long call becomes worthless, and the trader only the cost of the calendar.

Conclusion

A long option does not have an obligation attached to it.

Only short options have obligations.

By seeing in all scenarios what obligations have to be fulfilled at the expiration of the near-term option, we determined that all obligations can be fulfilled without incurring any extra cost other than the initial cost of the calendar.

This is provided that the trader maintains the long option for the entire duration while holding the short option.

The maximum potential reward of the calendar (the peak of the expiration graph) is only an estimate and can change as the trade progresses due to the volatility changing between the two options.

However, the cost of the calendar is the maximum possible risk of the trade at the expiration of the near-term option, assuming both options are closed at the expiration of the near-term option.

This number is fixed and does not change.

We hope you enjoyed this article on What is the maximum risk of a calendar options spread.

If you have any questions, please send an email or leave a comment below.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.

Original source: https://optionstradingiq.com/calendar-options-spread/